Quick, name a Hall Of Fame player that was also a head coach. It’s quite rare, actually. but if you take this test on a company’s sales or product group, the answer would be different. We often graduate the rock stars of business to middle management and beyond. That’s the bench strength program of the average organization.

Too often, though, the Peter Principle applies as the new manager struggles to make the leap from Rock Star to Director. Why? Because most stars are deeply scripted to focus on their personal improvement above all, so they can outwit and outlast. Many stars are also good team players, but that’s more about the give-and-take of strategy than it is coaching.

Occasionally a star player exhibit’s otherish tendencies, and that’s when and only when they should be promoted to coach the team (manage a group). Michael Jordan, who should know, once said: “It’s one thing to get better and better, it’s another to make everyone around you better.”

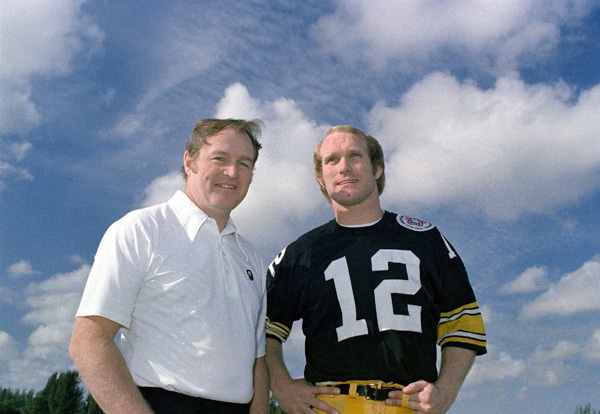

To offer a football analogy (It’s Fall, after all), that’s why so many of the top coaches in history were not rock star players: Bill Belichick, Tom Landry, Pete Carroll, Nick Saban, etc. Sure, they all played football in college, but they were not Pro Bowl caliber. Why were they selected to lead others? In every case, they were spotted as having two key coaching talents early on: They lifted up others’ performance and had a high football IQ.

That’s what should drive our management assignments. We should learn to ignore the individual performance and zero in on that leadersish style, combined with a strong sense of the business. When Jordan talks about the ability to “make everyone else better,” he’s talking about the ability to deliver the following:

- Education – The practice of gathering, distilling and sharing insights. Great managers are well researched, candid and enthused when others learn from them.

- Enforcement – The willingness to challenge those that stray off course. They enforce the culture and best-practices of the organization without fear of losing popularity.

- Encouragement – The tendency to be the first of the scene to cheer for someone who’s made a great play. When a team mate is down, they are there to pick them up and focus them on the next play. They find a way to balance empathy with an eye on the potential that lies ahead.

- Esprit de corps – The ability to lift an entire team’s spirit up, even in the most adverse situations. The great manager fulfills what Napoleon Bonaparte described as the leader’s role: “To define reality, then give hope.”

Marcus Buckingham, co-author of the management classic First Break All the Rules, directly applies this thinking to cube-farm living. He once told me that the superstars soar with their strengths, while the average performers struggle to conquer their weaknesses. The superstar manger, on the other hand, it the one that focuses the superstar on his or her strength to begin with.

Here’s the takeaway for leaders and HR professionals: Before you promote that superstar to the next level, question his or her leadership strengths. You might be robbing the system of several more years of top production, just to fill a mangement role with a strong resume. What you are looking for will not usually show up on paper, which means your ability to pick managers is going to be driven by your eagle-eye on others’ ability to lift up others rather than break records.